I didn't start out believing that secession of 11 western US states was a good thing. I didn't start down the path that led me to that conclusion thinking about matters of secession at all. I was thinking about several long-term trends related to energy supplies, technology, and population. It was only when I began thinking about those trends together that I began to see a longish-term future (25 to 50 years) where a partition of the United States looked like a sane -- and desirable from some perspectives -- thing to do. This post identifies the major trends, which will be expanded on in later posts. Those posts will also explain why I think the trends work together to lead to major changes.

The first trend is the decline in availability of liquid hydrocarbon fuels at affordable prices. I am not, in the vernacular, a Peak Oil "doomer": I don't believe that decreasing availability of liquid hydrocarbons will lead to a global collapse of civilization. OTOH, I do think that decreasing availability will lead to some dramatic changes in how the US looks at the world, and because the country is so large in a geographic sense, at itself. The changes will make the world a bigger place, and the US role in it smaller. Similarly, the US will also become a bigger place, with reduced linkages between different geographic parts of the country.

The second trend is the maintenance of the US electric grid. I am an unabashed fan of modern technology and want to see large parts of it preserved. The energy source that modern technology depends on most is electricity. Failure to provide robust reliable electricity supplies would render much of that technology unusable (eg, it's much more common to see articles that "developing country X's modernization attempts hampered by erratic electricity supplies" than to see that they're being crippled by higher oil prices). I believe that US electricity supplies face substantial challenges in the future, and that the responses to those challenges will have to be regional in nature. When policy makers think about "our" solutions to the electricity supply problem, those solutions will be different. In some ways, the policy decisions will create significant frictions between different parts of the country.

A third trend is the depopulation of the US Great Plains region. The population of the Great Plains counties peaked in the 1930s and has been declining ever since. In the last decade, the trend appears to have reached the point of positive feedback. The declining population has made it more and more difficult to support modern infrastructure and services, which in turn both drives more people out and makes it harder to attract new people, which makes it harder to support services,... An increasingly-empty 500-mile-wide buffer between the East and West portions of the US will lead to a decrease in "national" identity and increase in "regional" identity.

Another trend is global warming. I'm not going to bother with the "climate change" weasel wording: the important consequences of the changes for my purposes are a modest steady warming and effective drying of the US climate, particularly across the southern tiers of states. Warming (and more importantly, drying) will have multiple impacts that are worth exploring. By making agriculture more difficult in the southern Great Plains, it accelerates the depopulation. The problems that the already-arid Southwest will face will be different than those of the humid Southeast. As with some of the other trends, the result will be another factor pushing two parts of the country apart in terms of the policies that they will wish to pursue.

I believe that there are, for geographic and historical reasons, fundamental differences in the parts of the US that are east of the Great Plains and those to the west. One of the obvious geographic differences is illustrated in the map shown at the beginning of this post: the West is mountainous. As a consequence, it lacks long navigable rivers; the places where large cities can be located are limited; corridors where transportation (of people, good, or energy) can be located are limited. Sometimes those make things harder, but sometimes the limited population distribution makes things easier. In the course of these posts there will a number of maps of the 48 contiguous states along with assertions of differences in East and West.

This is a book-sized topic, so even a series of blog posts can't really do it justice. I'm working ( slowly) on the book.

Thursday, November 21, 2013

Thursday, November 14, 2013

Colorado Secession Vote -- With Cartograms!

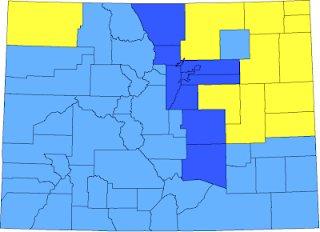

On election day, eleven Colorado counties included a non-binding resolution on their ballots stating that the counties should seek to secede from Colorado and form their own new state. I'm not one to let a secession-related event go unused, nor to pass on a chance to play with cartograms. This conventional flat map of Colorado is colored to show the eleven counties voting on the resolution in yellow, the counties usually considered part of the Front Range urban corridor in blue, and the rest in light blue. One of the original eight counties involved didn't get the item on their ballot (Morgan County, the single isolated light-blue county in the upper right quadrant) but four new counties joined up, including one in the northwest part of the state. Only five of the eleven approved the resolution, and all five of those were in the northeast group.

On election day, eleven Colorado counties included a non-binding resolution on their ballots stating that the counties should seek to secede from Colorado and form their own new state. I'm not one to let a secession-related event go unused, nor to pass on a chance to play with cartograms. This conventional flat map of Colorado is colored to show the eleven counties voting on the resolution in yellow, the counties usually considered part of the Front Range urban corridor in blue, and the rest in light blue. One of the original eight counties involved didn't get the item on their ballot (Morgan County, the single isolated light-blue county in the upper right quadrant) but four new counties joined up, including one in the northwest part of the state. Only five of the eleven approved the resolution, and all five of those were in the northeast group. The next map is a cartogram with county shapes distorted to represent their population rather than their physical area. With the exception of Weld County up along the northern border, the counties that put the resolution on their ballots are dwarfed by the Front Range. Comparing the two maps, it's clear that this is an urban vs rural thing. One of the Weld County Council members, who were the people that originally proposed the secession idea back at the end of the legislative session in May, recently spoke with Talking Points Memo and pointed this out explicitly: "And in this last legislative session we had what we call the assault on rural Colorado, the war on rural Colorado, where the urban-based legislature...". The three issues that seem to have upset the Council the most were modest gun regulations, modest renewable electricity mandates for rural coops, and some Front Range cities imposing a moratorium on hydraulic fracturing of natural gas wells within their city limits.

Let's zoom in on the ten counties in the northeast corner of the state that had the resolution on the ballot. Five of those ten approved the resolution by various margins and five defeated it. The counties are colored to show the split in the vote, with yellow votes for the secession resolution and blue votes against. I've adjusted the scale so that if 75% of the votes were in favor, the county would show up in the same bright yellow used above; if 75% of the votes were against, the county would show up in the Front Range dark blue; none of the counties voted that overwhelmingly in either direction. The five counties that approved the resolution are those that are the most isolated from the Front Range in the sense of greater distance and/or lack of interstate highway access.

Having lost the secession vote in six of eleven counties, the "rural power" proponents are moving on to other possibilities. They are now focusing their attention on various forms of what is being called the "Phillips County proposal" that would change the way districts are drawn for the Colorado legislature. The simplest of the proposals that has been put forward would give each of the 64 counties one representative in the Colorado House. Colorado counties range in population from San Juan County with 699 people to El Paso County with 644,964. All proposals of this type run smack into Reynolds v Sims, a 1964 SCOTUS decision that says each state is required to construct districts for its state legislature with as nearly equal population as practicable. The Court said explicitly that this applies to both houses of bicameral state legislatures; state senates can't enjoy the same kind of disproportionate deal the US Senate has.

Having lost the secession vote in six of eleven counties, the "rural power" proponents are moving on to other possibilities. They are now focusing their attention on various forms of what is being called the "Phillips County proposal" that would change the way districts are drawn for the Colorado legislature. The simplest of the proposals that has been put forward would give each of the 64 counties one representative in the Colorado House. Colorado counties range in population from San Juan County with 699 people to El Paso County with 644,964. All proposals of this type run smack into Reynolds v Sims, a 1964 SCOTUS decision that says each state is required to construct districts for its state legislature with as nearly equal population as practicable. The Court said explicitly that this applies to both houses of bicameral state legislatures; state senates can't enjoy the same kind of disproportionate deal the US Senate has.Even if the resolution had passed in all ten counties, and all of the required state- and national-level approvals were eventually given, it's not clear that "North Colorado" would achieve what the secession advocates think it would. Here's the same type of population cartogram for these ten counties that was shown for the state as a whole. In this view, it's clear that the new state would be "Weld County and the nine dwarfs." I've written elsewhere that this is something the dwarfs really ought to take note of. Weld County will be able to push them around in any legislature based on proportional representation (which Reynolds v Sims guarantees). Further, the reason that Weld County is so much larger measured by population is the more heavily populated western portion of the county: the city of Greeley and assorted suburbs/exurbs of the Front Range cities. Weld County is the fastest growing of the counties in both absolute and percentage terms. Several of the other counties in the group have shrinking populations. Suburban Weld County's hold on policy will only increase in the future.

It would be possible to carve out a Central Great Plains state from eastern Colorado, western Nebraska, and western Kansas that is entirely rural and small town in make-up. A state like the one shown here in yellow, producing four states of roughly equal physical size where there are currently only three. The area of the new state would be about 79,000 square miles, and the population would be about 432,000. As a point of reference, compare that to Mississippi: 60% more area but only 15% of the population. The three largest cities in the state would be Scottsbluff and North Platte from Nebraska and Garden City from Kansas. By most people's standards, these are towns rather than cities. The cartogram with county size representing population rather than area is interesting, with the new state crunched between the "behemoths" of Front Range Colorado and eastern Kansas/Nebraska.

It would be possible to carve out a Central Great Plains state from eastern Colorado, western Nebraska, and western Kansas that is entirely rural and small town in make-up. A state like the one shown here in yellow, producing four states of roughly equal physical size where there are currently only three. The area of the new state would be about 79,000 square miles, and the population would be about 432,000. As a point of reference, compare that to Mississippi: 60% more area but only 15% of the population. The three largest cities in the state would be Scottsbluff and North Platte from Nebraska and Garden City from Kansas. By most people's standards, these are towns rather than cities. The cartogram with county size representing population rather than area is interesting, with the new state crunched between the "behemoths" of Front Range Colorado and eastern Kansas/Nebraska. One of the problems with creating such a state — ignoring the quite real political difficulties — is that the new state would be very poor. Many of the counties that would go into the new state have shrinking populations. The infrastructure would be limited. Building and maintaining a new four-year state university would be a major challenge. All of those are serious hurdles to attracting the kinds of jobs that might help solve the poverty problem. I chose the comparison to Mississippi above on purpose. Overall, the new state would probably make at least parts of Mississippi look rather urban and cosmopolitan. I'm certainly willing to bet (my usual political-bet wager, a small beer) that within 10 years, 20 at the outside, the new state would discover that the cure was much worse than the disease.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)